what do you think about when you hear the world ‘minimalism’? do you think of art? do you think of architecture? fashion? design? or do you think about lifestyle and marie kondo and perfectly organized spaces with glass jars?

i think more often than not, i’m thinking about the type of minimalism where you try to get rid of all of your unnecessary belongings— the “things” that have seemingly no impact on your life. the things that you don’t need.

i spent a few weeks studying the origins of the term ‘minimalism’ itself–– aging back to the 1960s when it was used to describe artists like andre, judd, and flavin in their primes. artists who we praise now but were previously scorned by art critics for their mundane pieces.

carl andre, “lever” (1966)

donald judd, “untitled” (1965)

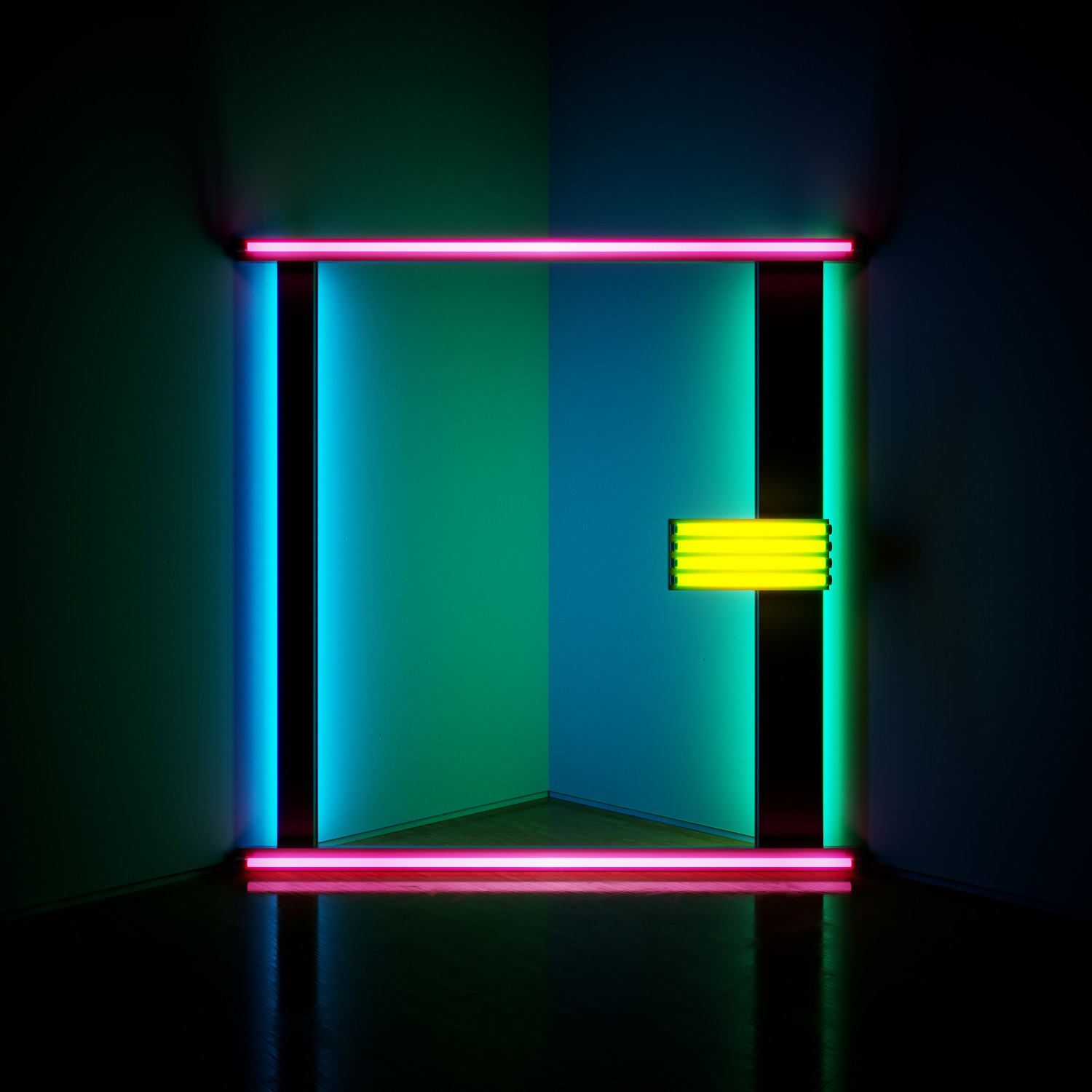

dan flavin, “untitled (to barbara lipper)” (1973)

even then, the term had this sort of air of entitlement: art in its most raw form was considered art in its most pure form. david raskin, a professor of contemporary art history at the school of art institute of chicago, said that for viewers, minimalist art provided the “opportunity to see the world without preconceptions.” i assume that he is implying that any other type of art makes us see the world insincerely..?

as i followed the transitions of the term ‘minimalism’ throughout the years, this “high-brow-ness” of the word endured, even after being adopted by other creative spheres: fashion, design, and architecture.

it was also – at some point, i remember – a tumblr fad. entire blogs were dedicated to posting photographs of pristine, white, angular interior designs and buildings. its look is sterile, almost to the point of discomfort. it seemed extreme.

i must say that as an artist myself, i’ve been guilty of trying to emulating this trend. minimalism just looks nice. it’s luxurious and clean—both physically and aesthetically.

but the reality of ‘minimalism’ isn’t all that pretty.

more recently, ‘minimalism’ has been crafted into an entire lifestyle. a lifestyle that, again, “leads to purity”… personal purity and self-fulfillment. how we live and what we own, according ‘minimalism’ activist marie kondo, indicates our “virtue and moral correctness.” so if we don’t live by her standards, we don’t have virtue? i’m getting that same sense of entitlement as the artistic connotation, no?

that’s just my feeling.

‘minimalism’ also becomes a socioeconomic issue because it is only truly accessible to those who have the financial cushion to buy back the things that they discard if they need them later.

“in order to feel comfortable throwing out all your old socks and handbags, you have to feel pretty confident that you can easily get new ones” — arielle bernstein, the atlantic

kondo underscores the “life-changing” psychological benefits of ‘minimalism,’ but doesn’t really acknowledge the environmental benefits that the lifestyle poses as well.

it’s obvious that we have a tendency to buy and own more stuff. but what does all of this stuff do to the planet? human product consumption contributes to almost 60% of global greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) alone. in other words, the more we accumulate, the more we contribute to GHGs.

‘minimalism’ is fundamentally about owning less. if we just own less, we can help alleviate these harmful emissions. we just have to make ‘minimalism’ easier for people to follow and broaden the scope of the term away from this new-age-y, high-end lifestyle to help “find our truest selves.”

we just have to be honest with ourselves and our habits. at its core, ‘minimalism’ is about being more conscious of the things we buy and why we buy them. if we adhere to that principle alone, i think it would be easier for people to get behind— both as a concept that promotes psychological sustainability as well as eco-sustainability. it doesn’t have to be about purity and moral virtue. it just has to be about mindfulness.

just a thought.

if you want to read my full essay in a more educational and unbiased format, you can find it here.

thanks for listening.

⌇